How Growth-Driven Design

Can Save Your Bottom-Line

Are you getting the most from your website?

Can you honestly say you’re getting the results you want?

Has it been worth the time, effort, and money, so far?

Would you call it successful?

Statistics suggest “no” is the likely answer.

“A staggering 70% of all web domains fail to be renewed after one year, according to new research into registration patterns across the most popular top-level domains (TLDs)”

Why is that number so high?

In this article we reveal the reason so many of these sites fail, and a framework to ensure your site doesn’t suffer the same fate.

If you’re in the middle of a site redesign right now, or even if you’ve recently completed one, this information will still benefit you. If you prefer, you can click [here] to skip to the bottom, and read the parts directly relevant to you first.

Whether from the data above, or personal experience, it might be easy to conclude that the website is to blame for any lack of results. Yet, if we look a bit deeper, we will discover that poor-performing websites are merely a symptom of the problem, not the root of it. We’ll explore that more as we go.

At the most basic level (unless we are talking about intentionally temporary web properties) it seems safe to say the 70% likely weren’t renewed because the site didn’t make enough money to justify its continued existence. I recognize it isn’t bullet-proof logic, but… why would anyone kill a website if it reliably generates significant profit?

At Wabbit, we like to back up our claims with data at all possible points but, seriously… if you had a reliable, money-making machine, would you really turn it off?

We wouldn’t.

And we bet you wouldn’t either.

That’s our data. That’s our proof.

So, our wager is the majority of those un-renewed 70% were financial failures.

The collective experience of the Wabbits (100% of the time) suggests these failures happen because there is something before the website that isn’t working. That mysterious, singular issue is the reason for every failure happening downstream. And if that root cause isn’t identified, no website in the world can fix it.

Aristotle, referring to such root causes, called them “the first basis from which a thing is known.”

Today, we call them First Principles, and their value can’t be oversold. Reasoning by first principles removes the impurity of assumptions and conventions. What remains are the essentials.

“I think it’s important to reason from first principles rather than by analogy. So the normal way we conduct our lives is, we reason by analogy. We are doing this because it’s like something else that was done, or it is like what other people are doing… with slight iterations on a theme. And it’s … mentally easier to reason by analogy rather than from first principles.

First principles is kind of a physics way of looking at the world, and what that really means is, you … boil things down to the most fundamental truths and say, “okay, what are we sure is true?” … and then reason up from there. That takes a lot more mental energy.”

— Elon Musk, FS.blog

He means: start with what is true.

We will talk about what is true of your website soon.

Deconstructing down to first principles — to the essentials — allows us to see what matters most, clearly, where reasoning by analogy alone might lead us astray. This mental framework clears the clutter of what we’ve told ourselves, allowing us to rebuild from the ground up.

When renown entrepreneur Derek Sivers founded his company CD Baby, he reduced the concept down to first principles.

Sivers asked, What does a successful business need?

His answer was happy customers.

(If you’ve been around the Wabbits for a while, you’ll know that was our conclusion too.)

A strong, profitable website (I’ll also call it a web asset) is one designed to attract people, to pull them in, to gather information from them, and to turn those total strangers into prospects and eventually, (happy) customers. Yet, if you were to search online for how to to build a site that can accomplish this critical series of tasks…

well…

Let’s just say, we haven’t found one yet either — which is the reason behind what we are doing here.

So we are going to talk about these roots causes, and how to build a strong & profitable website (through the lens of Jerry and Jasper).

Along the way, we are going to share critical first principles which, if internalized, have incredible potential to serve you well (across disciplines) for the rest of your life.

Ben Suarez, one of the great copywriters of the 90’s, was talking about printed advertorials when he said this, but it applies to our website conversation effortlessly, so, I’ll drop it in here…

“It should read like a “greased chute, with no dead spots in the copy. Once the prospect starts reading, he or she flies through the promotion and can’t stop.”

— Ben Suarez

The best, most profitable websites, are built like a greased chute for their audience. They are intentionally designed conversion machines — not some expensive gamble.

To the Jerry’s of the world, this process will look like little more than guesswork. Yet, by the end of our time together, you will know differently — and you will never want to go back.

Want to know the secret of profitable websites?

The big box website shops like Wix, Squarespace, and Godaddy are heavily invested in helping you see the need for a website, but (to put it bluntly) they don’t tell you shit about what really needs to be done once you have one.

Sure they have shallow blog articles and listicles that give an overview of a topic, but there’s no real guidance.

My commitment to you is: by the end of this piece, if you can notice and internalize the first principles at work right in front of you, you will never feel lost about how to approach your website again.

Knowing we need to have a website, and knowing what that website needs to be, are not the same thing.

That’s the reason experienced agencies begin the design process by establishing goals. We always start by asking about what goal the site needs to achieve. and it sounds simple, but, there’s a a danger lurking in the corner of the room — and the average agency apparently isn’t interested in warning you about it…

Without the right approach we risk our website being a complete waste of time and money — little more than an expensive vanity project.

Even if we temporarily forget the technology decisions, there are plenty of wrong ways to build a website. The process can easily become expensive, fast — and there is no guaranteed return.

We can avoid this, but, at minimum, we need to realize:

- A website is a critical component of a marketing strategy, it shouldn’t be the entire marketing strategy

- You cannot hack together compelling parts of other people’s systems and expect it to produce a sale, it doesn’t work like that.

Rather than blindly throw darts, we need a systematic approach that extends our budget and increases our odds of success.

As luck would have it, that’s exactly what you’re reading about!

Before we get into that systematic approach, I need to level with you…

The challenge is the mindset, not the website

If we were to look over Jerry’s shoulder as he works out what to do about his poor site performance, we would see him building a Franken-tactic marketing monstrosity.

He needs leads, or sales, or anything positive to come from having this site, so he inevitably throws every idea he can think of at it. He has everything:

- Headline formulas that worked well for a friend’s business

- Some “proven copywriting formulas” he found online for the ads

- Landing page templates with “guaranteed conversion rates”

- Newsletter opt-in pop-ups

- Abandoned cart sequences

- the works

But it won’t work.

Jerry doesn’t operate from first principles, he behaves like an opportunist. A tactic-hopper. He sees the latest marketing trend, tries it out, and after weeks or months of lackluster impact, he abandons the idea altogether. Inevitably, he throws his hands in the air and makes the wrong conclusion.

“______ doesn’t work for my business”

The truth is, Jerry can’t simply look at what others are doing and give it a shot himself.

Mimicking the status quo isn’t good enough.

The problem gets worse if his business (to him) appears to be running just fine without some fancy-pants website.

In this case, he may not be wealthy, but he does have revenue. Plus, in his past experiences, he’s spent a bunch of money for very little return.

We can see exactly why he would think this too. From Jerry’s view, the conclusion makes sense. We empathize with him. He has something that’s working and, so far, nobody has shown him how to easily get more value from it. Why mess with it?

Because there’s a big difference between the average contact form, and a landing page converting at a humble, yet reliable 25%.

If Jerry could see how to turn his website into a 24/7 passive revenue generator, our bet is that he would shift from preaching about how his website didn’t work for him, and start asking serious questions about how to MAKE it work for him.

The marketer in me wants to make you wait for the big reveal…

I won’t, it isn’t the biggest revelation on deck.

The simple truth is: the most successful websites resonate with their audiences powerfully. I’d give you a bunch of proof here, but (like before) there’s no need. You are my proof. I’ll demonstrate…

Ask yourself, what websites (apps count too) are you on most?

Why those?

The unique “why” behind your habitual use of certain sites is far too unique for me to nail in a post like this, but… I’m willing to wager that the word “resonates” is a reasonable way of describing the magnetic pull. You keep going back because the site resonates with you on some level.

That fact is worth paying attention to.

The very first step in building a site which resonates with an audience, is to be able to clearly identify that audience. To do this well, accurate data is required. It helps us ensure we set the right goals.

Jerry disregards, or doesn’t collect the data necessary to do this. He completely misses the value of it.

Even without sales or leads, data is a goldmine

Because of his overwhelming focus on money, when Jerry thinks about business, he only sees the sale, that’s all that’s in his awareness. Customers are a necessary step along the way to profit, in his eyes. On his best day, when Jerry sees a website, all he sees is a lead generator, or a sales funnel.

On his own site, if he has one, the overwhelming focus is on sales and telling people “what we do.” Same with social media. In the rare cases that he looks at his traffic data, Jerry looks at page views and doesn’t pay much, if any, attention to the rest.

He forgets, it was data that turned Facebook and Google into titans.

I’ll give you the broad-strokes in an example:

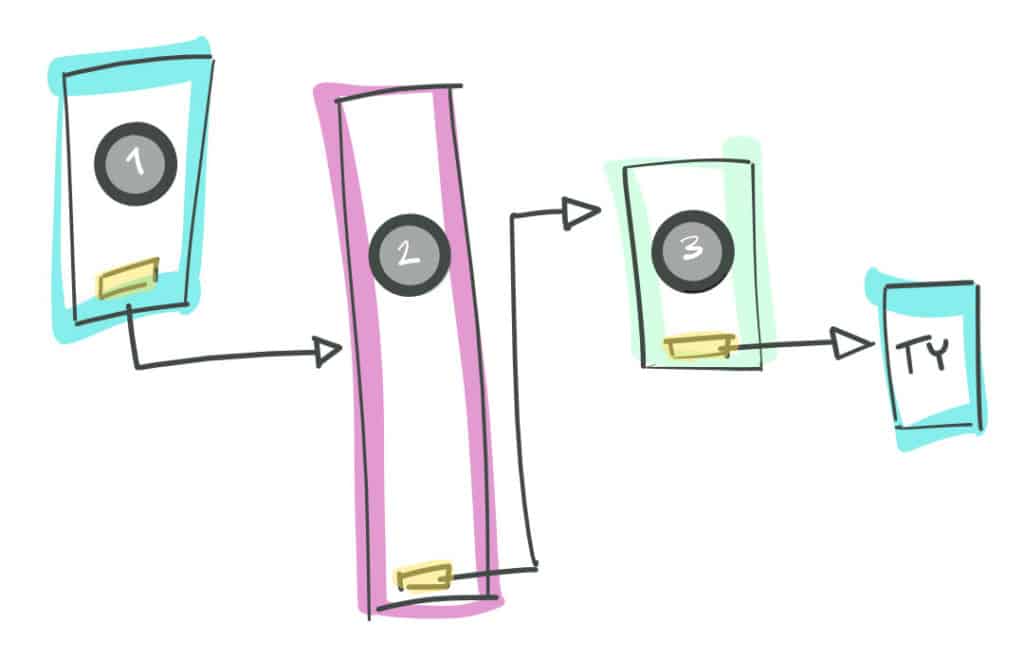

Imagine we lay out a series of pages as a sales sequence. The goal is, by the end of the sequence, the visitor buys the offer. At a high-level view, it could look something like this:

Over-focusing on the sale at the end of the sequence means Jerry doesn’t see the real treasure sitting in front of him. He’s never heard of the Discovery process, or heat maps, or funnel sequences, and he isn’t sure why he should learn any of it.

Look at the previous graphic and imagine we find an insight in the data. The insight suggests we are losing a significant number of people in the middle of page 3. If I am looking for levers that affect sales at the end of the sequence, this insight is a great place to start.

And it is only the beginning of what we can learn.

Where Jerry only sees the sale, Jasper sees a vast testing ground for building an automated revenue generating machine.

Jasper hones his offers through the crucible of his data analysis. He knows it is the most reliable way to discover the offers that work reliably. He doesn’t see a dip in traffic on page 3 as a failure, he sees it as valuable insight.

Leo fails forward.

Thomas Edison, after inventing the light bulb, received a question about failure from a reporter. The reporter asked how he was able to persevere through all his failed attempts along the way.

Although it has proven difficult to track down Edison’s exact replay, it is generally agreed that he responded with something like this:

“I didn’t fail 1,000 times, I learned 1,000 ways not to make a light bulb.”

— Thomas Edison

Yet, what would Edison have learned if he had never taken notes, or recorded the results of his experiments?

In the world of websites, analytics (our data) are the results of our experiments. And we can’t reap any benefits from these results if, like Jerry, we are unable to recognize their value.

Build a better foundation first

The average experience of getting a website made, or redesigned, is AWFUL. Anyone who has shopped for a website has heard (or experienced) the horror stories.

The summary: It takes months of strategy meetings, and then content meetings, and then revision meetings, and then launch meetings. It costs and costs and costs. And, if the thing ever gets done, the juice isn’t usually worth the squeeze.

We’re talking sites that have no hope of paying for themselves, let alone becoming a significant source of revenue for the owner or the business.

Jerry knows this, so he’ll put his site off and focus on other things. He doesn’t bother with the cost research. He doesn’t bother trying to understand the value a good web asset can bring. He firmly believes it will cost more than he wants to spend, for less return than he would like.

I’ll stop picking on our man for a moment, and go broader instead.

Let’s say an organization decides it’s time for a new website. All the stakeholders get involved, they bring in a skilled external firm, and together they figure out the strategy, content, messaging, and style.

Several months later, the site launches and everyone loves it. Feedback is over the moon. A smashing success.

Yet, if we check back a year later, the grumblings have already started.

By year 3, staff talks openly about how terrible the website is. And by year 5 it’s universally considered a complete disaster — an unsuccessful embarrassment. So, it is torn down and rebuilt from scratch. And (roughly every 5 years) the cycle repeats…

it’s a cycle we’ve all gotten so accustomed to, it can be hard to remember how broken it is.

What’s really needed is a better foundation.

The critical shift is realizing that the completion of the website is not the finish line, it is the starting line.

Jasper understands his site needs to continue to evolve in order to stay relevant, useful, and effective. He builds that evolution into the system from day one, because he knows how to iterate his way into a profitable asset.

Jasper leverages quick, small-scale, budget-friendly tests to help the asset evolve in profitable directions. He then uses the profits from these tests to fund the next round of tests. In this way, at his best, Jasper is able to fund the continual growth of the asset iteratively, and potentially indefinitely.

Traditional web design would have us make a fully realized site before launching to the public. Yet, by adopting more nimble concepts, we can save money, and move faster, because we have rock-solid intel on what is needed.

Data Drives Decisions

Our friend Jerry sees all this website talk as a hassle because he doesn’t yet see how the value applies to his unique situation. If he were a local plumber with a small business he’s run for 20 years, we might imagine him saying things like:

- I’ve been doing this for decades, I’m already an expert

- I already know what my customers want

- I already know what we (the business) need

To an extent, he would be right, and we ought to respect that. In fact, he may know with perfect clarity what his current customers are looking for.

Yet, hunches, feelings, and intuition aren’t enough. Even if Jerry is absolutely right, we still want the data in a hard format so we can mine it for insights over time, and at multiple levels of detail.

If I were talking to Jerry now, I would ask…

- Are his customers sure they know what they want?

- Does he know what his prospects want?

I’m not looking to convince Jerry that he doesn’t know his people, that would be silly. I’m demonstrating that there are more questions, nuanced questions, deeper questions to ask.

It isn’t enough to know there’s gold in the hills — we need to know where, exactly.

Good data acts like clues, or points of interest on a gold prospector’s map, helping us discover insights, and places of maximum potential.

In our gold-hunting journey toward the dig site, the weather will shift and change daily, or faster. For Jerry, these weather patterns are the fly-by night marketing tactics littering the internet. When he cobbles trends together into his Franken-tactic website monster, he is reacting to the weather, rather than preparing for it.

Beyond simply pointing out the gold on the map, good data lets us anticipate, and build sound strategy for moving toward our goal, regardless of the weather, rather than blindly chasing our tails along the way. But how do we decide when we have enough data to act?

Perfect is the enemy of good

Without being sloppy, the fundamental mindset is: reach a point of “ready to test” as quickly as possible. For some, this may mean they need to set ego and assumptions aside — for others, it may mean starting simpler.

In the Lean Methodology, the big idea is illustrated with the “build > measure > learn” feedback loop. To describe the cyclical process of the loop, we like the term iteration.

Each time around the feedback loop is one iteration.

Note: Wabbits think of iteration as a series of sprints. Unlike the traditional approach to web assets (where the “build > measure > learn” process can take a year or more) we love moving fast — so, we like to keep our cycles running at 4 weeks or less. That’s us. That’s the amount of time that we try to complete ours within. Let’s be clear though…

The specific length of time isn’t as relevant as the principle underneath.

For us, “staying lean” means keeping ourselves fast and nimble.

It means using the ancient secrets of not building stuff without asking people what they want along the way.

It means building incrementally — iteratively — instead of trying to build everything at once.

Software developers call the process “agile development.”

The rhythm should be as fast as can be maintained without losing control of quality. But… what level of quality?

Jasper knows procrastination masquerades as perfectionism, so he finds his best rhythm by allowing for a little imperfection. Rather than striving for an arduous, taxing goal of 100% perfect, he allows for a quicker, looser 90%. Good enough to test with and quickly generate some useful results.

Contrary to what Jerry has convinced himself, the public doesn’t demand we blow their minds with a “perfect site” on day one. The public only demands that the site exist, and that it work on their device.

Jerry’s mindset that any specific feature is critical before a site (or an offer) can go live and generate feedback isn’t true, or helpful. Especially not when trying to make a reliably profitable web asset. In fact, the mindset will often cause Jerry to spend too much, and take too long in the process.

Jasper is confident in setting his fear (and ego) aside because modern technology allows him to fix any errors quickly. Rather than worry about mistakes, he focuses on creating a living website whose growth is based on how real customers and prospects use it.

A site which evolves steadily over time, guided by the simple wisdom of listening to people.

I mentioned a moment ago that Wabbits operate in sprints. Improvements made to a site during a sprint are NOT based on the whims and ideas of the marketing or management teams. They aren’t based on the CEO’s hunches either. Any and all changes are rooted in understanding traffic sources, and how visitors are using (and not using) the site.

We make improvements based on a strong foundation of robust data which educates us about real-world user experience.

Some examples:

- Reducing the number of “required” fields on forms to improve conversions.

- Decreasing the rate that users leave the site by inter-linking to highly compelling content.

- Incentivizing a call to action to increase lead generation.

These are heavily generalized examples but, the point is: We aren’t trying to nail all the possibilities in our first shot. It isn’t possible.

Trying to do so is likely to increase costs in time and money — and, we are going to miss a lot. Instead, we are trying to zero in on a target over time. Like a game of Battleship.

In fact, let’s build off the battleship analogy, swap in some pirate ships canons, and a playful headline, and explore the idea…

Size matters, don't start too big

In his book Great by Choice, Jim Collins uses the idea of a 1-on-1 pirate ship battle (we like to imagine it happening in a thick fog) to illustrate a concept he calls “Bullets first, then cannonballs.” Here’s a summary of the idea from his landing page on the topic:

“First, you fire bullets (low-cost, low-risk, low-distraction experiments) to figure out what will work—calibrating your line of sight by taking small shots. Then, once you have empirical validation, you fire a cannonball (concentrating resources into a big bet) on the calibrated line of sight. Calibrated cannonballs correlate with outsized results; uncalibrated cannonballs correlate with disaster. The ability to turn small proven ideas (bullets) into huge hits (cannonballs) counts more than the sheer amount of pure innovation.”

— Jim Collins

Those conceptual bullets Mr. Collins is talking about are the Minimum Viable Product (or offer, or website). They are the build phase of the “Build > Measure > Learn” feedback loop.

The fuel for the flywheel.

Jasper sees this, so he fires his best shot, his best first guess in the fog — and every next MVP bullet is adjusted, based on what he learned from firing the one before it. He doesn’t waste resources by trying to do too much too soon. This is how he stays agile and budget-friendly.

Phase one of Leo’s new website is the first run around the flywheel. It’s a draft, it is imperfect.

He launches it anyway.

He measures how people use it.

Where are they coming from?

Where on the site do they linger for a while?

How many filled out his contact form?

He learns from this data…

Makes the second draft…

Measure the response…

Learns.

Build the third draft.

The fourth.

The eightieth.

Relentlessly.

At first, it’ll be a slow process. It’ll take more time than we would like before we see the traffic, or gain the results we hope for.

That’s part of the process.

That’s how flywheels work. This isn’t just true conceptually, it’s true of the fundamental engineering of the thing.

To illustrate this, check out the video below. In it, you’ll see a very strong man start an entire tank using a flywheel.

It takes lots of energy to get them moving, and then, eventually…

The inertia carries itself.

This is a profoundly important concept.

It is worth noting that Jim Collins is credited with teaching the flywheel concept to Amazon’s Jeff Bezos, who acknowledges it as one of the primary factors contributing to his incredible success.

It is the same mental model powering every case study at Wabbit.

Jasper knows honing a powerful website takes time, and data. He approaches his web asset as a refining test because he’s spent the time learning about lean/agile concepts like these, and how they apply to his business.

He recognizes the power of running lean and embracing nuance, so, he gathers as much data as he can from his testing efforts, and he asks specific and insightful questions of it. This helps him better calibrate the aim of his eventual offer.

How to never wonder what you need again

In the Socratic dialogue Republic, Plato famously wrote: “our need will be the real creator.” Over time, this evolved into the English proverb “necessity is the mother of invention.”

Applied to our topic, this idea means need will dictate the shape of the eventual web asset. Data-driven approaches allow us to focus on need, and make only what is widely valuable to our people.

That point is utterly critical to understanding, and replicating, the success we Wabbits have generated for so many of our customers.

Systems theory can help Jerry see that any business is more than a collection of parts. This fact is the root of why his Franken-tactic approach isn’t working for him.

We can’t just take the best parts from the best cars and bolt them together to make the ultimate best car.

It won’t run.

All systems are more than a collection of their parts. They are the emergent properties of the interactions between those parts.

Read that again.

Jasper understands there are near-countless ways of gathering direct and indirect feedback. Rather than wondering about what to do next, he uses his data to direct the next small, precise, iterative test.

His mental framework enables the business to make only what is widely valuable to his tribe of customers and prospects.

The iterative nature of the feedback loop principle provides clear data about what is needed, by what portion of the audience, how urgently, how often, and so much more.

Ideally, this growth-driven feedback loop is always running.

- Constantly gaining data.

- Constantly updating itself.

- Constantly checking the data to see which changes to keep, and which to revise.

Jasper doesn’t have to worry about knowing what he needs, or what to do next, because (if he pays attention and trusts it) the data will tell him.

As he asks his data if the effort succeeded, the site will grow and change accordingly.

How to make ideas EVOLVE into assets

Imagine Jerry as a founder trying to launch an online course. Write down your answer to this question:

Does he need to have the course finished (or at least started) before he can start selling it?

Reflect again on the idea of bullets before cannonballs. When I mentioned allowing for imperfection, I wasn’t only talking about typos. Not only can the entire MVP can be imperfect, Kickstarter proved we can sell the idea before we’ve made anything. This fact matters for more than startups. Remember…

MVP stands for:

- Minimum – Most rudimentary, bare-bones foundation of the solution possible

- Viable – Sufficient enough for early adopters

- Product – Something tangible that customers can touch and feel (or, in the case of digital goods, use at a minimal level)

It represents the absolute minimum you can make to test your idea, and gain feedback.

It helps you quickly identify what customers really want.

And what they don’t want.

Our pal Jerry over-focuses on the product (or idea), because he believes success comes from an elusive intersection of the right place and time. To him, once the stars align, he’s ready to build the big, revolutionary idea (before validating it), and he just needs a loan to make it happen…

It’s a mistake so common that we accept is as normal behavior.

In Company of One, Paul Jarvis has this to say:

“Often, complexity can creep in right from the beginning – when you’re just thinking about starting a new business. You begin to assume that your business requires “essentials” like office space, websites, business cards, computers, fax machines (just kidding), and custom software solutions.

In reality, it’s usually possible to start a business – especially the freelance or startup kind – just by finding and then helping a single paying customer. Then doing it again, and again. And only adding new items or processes to the mix when they are absolutely required.

If you have an idea for starting a business that requires a lot of money, time, or resources, you’re most likely thinking too big.”

— Paul Jarvis, Company of One

Once you see the first principle at work in what Mr. Jarvis is saying, you won’t be able to unsee it — and It can affect the way you look at business forever. The scope and depth of content on your site can grow, adapt, change, and evolve based on your goal, and what it encounters in reality.

Isn’t is interesting that it sounds like the same principle powering life on Earth? Almost like it’s a universal truth or something.

Because Jasper applies such fundamental truths to his web asset approach, and uses data to drive development, he uses foundational testing tactics like split-tests to create his top-performers over time.

The more he internalizes these principles, the more he senses how this conceptual framework can ripple through the company.

Each of us has a finite supply of time and money. None of us can change the first fact. Leo is working on changing the second. In order to do so, he will want to be wise with his resources, so…

Save money, be wrong less

Operating from a data-driven philosophy ensures we stay wise with our resources while building any offer, product, site, business, etc. We begin our process by accepting the inevitability of being wrong in our assumptions — because we know not every point of interest (on the map that is our data) will lead to gold.

That’s the big “why” powering Jim Collins “bullets before cannonballs” idea.

This growth-driven feedback-loop principle exists in virtually every industry on the planet today because proper testing and validation keeps companies safe from over-investing time and money in unprofitable areas.

Because he operates from hunches and anecdotal evidence, Jerry doesn’t know what he really needs for growth — so, he is perpetually concerned about being sold on something he doesn’t need, and being over-charged for it in the process.

Yet, Isn’t it strange then that he won’t hesitate to exhaust his resources launching some big, fully-formed idea… to near-zero interest.

Who hasn’t heard a horror story about insanely expensive websites amounting to little more than massive wastes of time and money for the Jerry-run businesses who had them built?

Jasper, on the other hand, understands that offers are rarely born perfect (or successful), and that they need to be tested and honed before they can achieve anything close to their peak performance. He knows this fact means he will be wrong a lot, and he (like Edison) trusts that eventually he will find his target in the fog.

Growth-driven design is powerful and popular among experts because of the inherent need for testing and honing when developing a product. This approach uses simple tactics (like a/b experiments, etc.) to generate strong, valuable insights, and help avoid costly mistakes during the development of a web asset.

We can trust this isn’t some new fad tactic because, at the most basic level, we are leveraging the natural mechanics of “survival of the fittest” to build our best, most profitable web asset.

This is the same principle which gave science (the concept of it) to humanity, and it’s the same principle powering Jerry’s fantasy football bracket on Tuesday nights.

“Often, complexity can creep in right from the beginning – when you’re just thinking about starting a new business. You begin to assume that your business requires “essentials” like office space, websites, business cards, computers, fax machines (just kidding), and custom software solutions.

In reality, it’s usually possible to start a business – especially the freelance or startup kind – just by finding and then helping a single paying customer. Then doing it again, and again. And only adding new items or processes to the mix when they are absolutely required.

If you have an idea for starting a business that requires a lot of money, time, or resources, you’re most likely thinking too big.”

— Paul Jarvis, Company of One

Once you see the first principle at work in what Mr. Jarvis is saying, you won’t be able to unsee it — and It can affect the way you look at business forever. The scope and depth of content on your site can grow, adapt, change, and evolve based on your goal, and what it encounters in reality.

Isn’t is interesting that it sounds like the same principle powering life on Earth? Almost like it’s a universal truth or something.

Because Jasper applies such fundamental truths to his web asset approach, and uses data to drive development, he uses foundational testing tactics like split-tests to create his top-performers over time.

The more he internalizes these principles, the more he senses how this conceptual framework can ripple through the company.

Each of us has a finite supply of time and money. None of us can change the first fact. Leo is working on changing the second. In order to do so, he will want to be wise with his resources, so…

Work from principles, not marketing hacks

By reasoning from first principles, Leo has learned to break down complicated problems into their most basic elements, and then reassemble them from the ground up. He applies this in all areas of his life, including his website.

Jerry can choose to do the same.

He can learn to adopt Leo’s mindset.

Rather than worrying about writing the about page, or launching a sale on his shop, he can focus on building a stronger foundation.

Rather than working from his gut-feeling or hunch, he can gather, review, and understand the data his website can generate for him.

Rather than thinking of the website as the finish line, he can acknowledge it is only the beginning.

Websites generate revenue best when they are positioned well in relation to the pocket of people they aim to serve. That’s the target to aim at.

In a broad sense, that target is called product-market fit, and Marc Andreesen, the famous American entrepreneur, has this to say about it:

“I believe that the life of any startup can be divided into two parts: before product/market fit (call this “BPMF”) and after product/market fit (“APMF”)

When you are BPMF, focus obsessively on getting to product/market fit.

Do whatever is required to get to product/market fit. Including changing out people, rewriting your product, moving into a different market, telling customers no when you don’t want to, telling customers yes when you don’t want to, raising that fourth round of highly dilutive venture capital — whatever is required.”

— Marc Andreesen

The iterative feedback loop is the vehicle we use to obsessively focus on product-market fit for a web asset. We use this feedback loop, at all levels, to discover and test “whatever is required” of any asset, web included — and we perform these tests relentlessly.

We test with inexpensive bullets, and when we find the target we want…

For those going the DIY route, you’ll pay for your growth as you need it.

Internalize the words of Paul Jarvis, and remember: if it costs too much, you’re probably thinking too big.

Maybe instead of that crazy form you’ve been thinking of… maybe you add your 10-100 customers into a spreadsheet by hand. Sure, it’ll be a burden.

Use that as motivation to turn a profit. Once you’re making money, reinvest in improving your process.

Profits fund the growth.

Broadly speaking, if you’re hiring someone, you can either pay in milestones, or pay up front. The nuance of the arrangement will depend greatly on what the agency/freelancer offers, so I’ll leave you with some guidance…

The complexity of your minimum viable website will determine what you pay. This ought to be a strong motivator for finding ways to implement a lean approach. Anyone you hire will need to understand, and be onboard with this approach.

Expect to be charged an upfront fee, and, if the web designer offers it, consider a growth retainer over the traditional hour-based retainer to handle the ongoing work. If you want to learn why, we talk about it here.

We can reach a better product-market fit more efficiently when we leverage our website (and the data from it) to drive our decisions, and our growth. Principles like this aren’t just for big companies with bigger budgets. They work universally.

That’s why we so passionately believe this approach is the most effective way to build nearly any small business website.

If I want the biggest return on my investment, the lowest barrier to entry for testing an idea, and the most efficient use of my time and money, my web asset needs to be built from growth-driven principles.

PS:

If you’re thinking “Yeah, but we just redid our website,” or “My site looks good. I don’t want to change it,” we understand your position!

Here’s how to a GDD approach looks in those scenarios…

#1: You just redid your website

Perfect! This means there probably isn’t a ton of work to do on your first sprint cycle. We can probably move right on into collecting user-data.

What you’ll likely find, if you went with a more traditional approach to web design, is that some pages are functionally irrelevant to your audience.

You might find, for example, that while your entire company is enamored with your “Our History” page (and the beautiful timeline that took so much effort to build), prospects don’t care and aren’t reading it.

Realizations like this can be emotionally challenging but, the data isn’t going to lie to you.

User data will quickly tell you:

- where content needs to be revised

- where you are losing your user’s attention

- what kinds of content they want more of

- what features they want or don’t

- etc.

The full list of things we can learn from your users is really, really, really long.

#2: You love your current site's look

Also perfect! We don’t want you to start over if it isn’t necessary. We don’t even want to suggest it!

The look of your site (while important to branding, appeal, and recognition) shouldn’t be the focus. It matters, no doubt. However…

The absolute most critical thing is the experience your prospects and customers are having on the site. Your existing traffic and usage analytics will likely uncover a lot of quick wins, and help to develop a plan for long-term improvement.

The point is this: No matter what that state of your site is today, it will serve you better if the data it generates is actually being used for something.

So, when we say Growth-Driven Design, we are giving you a term that encompasses a flat-out smarter approach to web design.

It eliminates the headaches.

It eliminates the risk.

It makes your site steadily more useful to your audience, and therefore more useful to your business.

Wabbit breaks this process into phases that are designed specifically to be cycled through quickly, and frequently, funding themselves through their own demonstrated profitability. You can see examples of this throughout our case studies.