Understanding Your Audience

Pixels & Profits: Chapter 1

Why Your Audience Matters

“Know thy audience” — a mantra echoed throughout every successful marketing agency on the planet, and for good reason. In every industry, gaming included, the single most important variable in the equation of success is alignment with the target audience.

- Who are these people you’re designing your game for?

- What are their interests, motivations, and behaviors?

- Why are they unhappy with their current selection?

- How would they articulate what they want in a game?

To answer these questions, you will need to work to understand your audience at a deep and intimate level — to the point where you know their hopes, their dreams, their motivations, and even how they think.

The gurus of Reddit, etc. will tell you “just make a marketable game”…

That advice is backwards.

You can’t reliably make a “marketable game” without a deep understanding of your audience.

Busting Misconceptions: The Audience Comes First

Instead of building our business (or game) first and then hunting for customers, we focus on a very narrow group of people from the start, and build based on their needs.

By the way, if you’re auto-rejecting this idea based on some perceived creative restriction… Consider for a moment that I’m using cartoon bunnies to teach you about the highly complex systems of building wealth and freedom through entrepreneurship.

The restrictions you perceive do not exist in our reality.

They are the result of a cripplingly unhelpful mindset.

The truth is, getting to a working business model in any industry begins with understanding the big customer problem — but this isn’t where most people start.

In The Big Idea, Ash Maurya says this:

When we first get hit by an idea, the solution is what we most clearly see and what we spend most of our energy towards. But most products fail – not because we fail to build out our solution, but because we fail to solve a “big enough” customer problem.

My experience coaching entrepreneurs over the last decade has proven what Ash is saying. All too often, I see an over-focusing on the idea from companies of all sizes.

More often than not, these companies see their product as solving a clear problem (or offering a clear benefit) for the marketplace, but…

They’ve failed to ask themselves if the problem is big enough to build a business with.

(stick with me, I’ll tie this to game dev in a second)

A Shift in Perspective:

Jobs to Be Done (JTBD) Theory

Too often, when our idea first comes to us — when we have that flash — the big solution captivates us, and we forget the first principles powering success.

One of those principles is called Jobs to be Done (JTBD).

JTBD theory, published in the Harvard Business Review in 2016, says this:

We all have many jobs to be done in our lives. Some are little (pass the time while waiting in line); some are big (find a more fulfilling career).

Some surface unpredictably (dress for an out-of-town business meeting after the airline lost my suitcase); some regularly (pack a healthy lunch for my daughter to take to school).

When we buy a product, we essentially “hire” it to help us do a job. If it does the job well, the next time we’re confronted with the same job, we tend to hire that product again. And if it does a crummy job, we “fire” it and look for an alternative.

(We’re using the word “product” here as shorthand for any solution that companies can sell; of course, the full set of “candidates” we consider hiring can often go well beyond just offerings from companies.)

Jobs-to-be-done theory matters because, when we approach business building from the perspective of a customer’s desired outcome, it transforms our understanding of customer choice in a way that no amount of data ever could, because it gets at the catalyst behind a purchase.

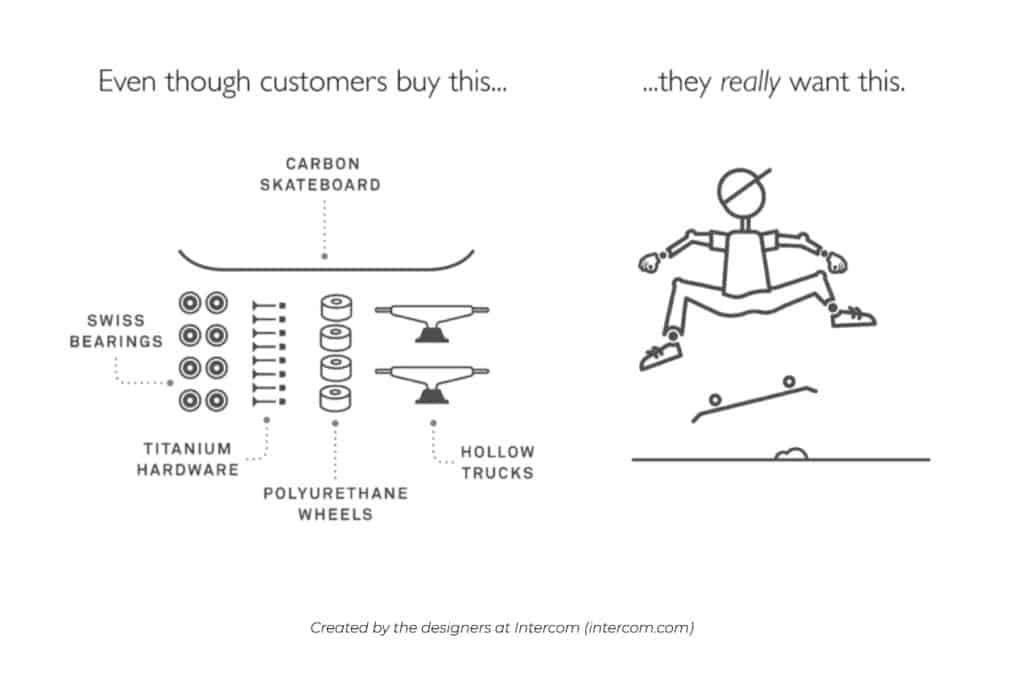

The designers at Intercom use this graphic to illustrate the point:

This is a profound shift in thinking for many.

We could easily replace that graphic with representations of mechanics in any given indie game.

Understanding that one simple concept can be the difference between your game becoming the next indie darling or disappearing into digital obscurity.

The goal is to give your people what they really want, not a random assortment of game mechanics.

Meaning that you need to address the catalyst behind the purchase, not the feature-set.

Real-world Example:

The Stunning Rise of “Among Us”

The indie game “Among Us”. Released in 2018, it initially garnered little attention. However, its developers, InnerSloth, understood that what they really needed in the beginning wasn’t necessarily sales, it was feedback.

They used that feedback to hone their game, aligning it more and more to the needs and desires of their audience. Then, with the game tested and dialled in, they increased their traction via a few niche streamers with large enough followings to move the needle.

Throw in the “luck” of a global pandemic where everyone’s quarantined and craving some kind of fun interaction with others — and you’ve got a viral sensation played by, at its peak, half a billion players.

Of course, there’s more to the story…

During the rise in popularity the Washington Post, interviewed Forest Willard, one of the Among Us developers. When asked how to make a game go viral, Forest said this:

“Make a small game. The smallest possible game. Just so you know everything that goes into it. A lot of people come up with these big ideas, and they think they’re going to make a huge game. And then you get some amount into it, and you lose your way. And then you don’t ever actually make a game at all. So if you’re just starting out, just make something super tiny. Just focus on something very, very simple and make that. That’s how we got our start.”

— Forest Willard

We will come back to this subject later but, Forest is talking about building what we marketers call a “Minimum Viable Product,” or MVP for short.

The key to creating a successful MVP is…

I bet you guessed it…

Understanding your audience!

But, if you read that article from the Washington Post… it kinda sounds like they lucked into becoming a global sensation, doesn’t it?

By Willard’s own words, InnerSloth “suck at marketing” and knew going into the release of “Among Us” that they weren’t going to attract a whole lot of attention.

They tried tweets here and there and received some feedback, but not enough.

And then the right streamer found it, broadcasting the game to his 30,000 followers during a global pandemic.

And thus – “Among Us” became the new indie game sensation, joining the likes of Flappy Bird and Wordle as global phenomena.

None of it was planned.

I intend to help you find your success on purpose.

And you won’t need global virality to get there.

Objectivity is critical though.

Especially while researching and identifying your target audience.

Because it’s too easy to fall into the trap of trying to create a game for an audience of “everyone.”

Avoid the "One-Size-Fits-All" Trap

As you dive into audience understanding, beware of the “one-size-fits-all” trap. While it’s tempting to aim your game at “everyone,” successful games are those that address a specific audience’s needs and interests.

A game that pleases everyone (or just most people) doesn’t exist.

Even Minecraft — a game enjoyed by millions — has a well-defined, hyper-focused target audience: creative individuals who enjoy sandbox experiences and building.

The common concern sounds something like this:

“But what if I niche too narrow and miss potential customers?!?”

If that is you, I want you to remember that there are 8 billion humans on the planet. Even if you niche down to 0.0001% of the global population, and sell those people a game for a measly $1 — you’ve still made a fortune.

The significance of knowing your audience isn’t confined to the game’s concept or design. It plays a major role in marketing your game effectively too. After all, marketing, as we Wabbits know it, is the literal first step in making any product.

How can you tell people about a product if you don’t know who you’re selling to?

How can you know what they want if you’ve never spoken to them?

Making anything without first stopping to seriously consider who it is for is like trying to hit a target from three miles away, while you’re blindfolded and standing in a blizzard.

I’ll say it again just to be clear:

Before you can create a product, or a marketing strategy, or an offer, service, etc. you need to understand your audience.

It is the only reliable way of creating work that speaks to them and, more importantly, motivates them to buy and play your game.

Okay, I’ve beat that point into the ground.

So your audience isn’t everyone. Then who?

Demographics vs. Psychographics: Painting the Whole Picture

I’ve hammered home that you need to understand your people but, the truth is, that’s pretty normal, surface-level advice. Our research showed an astounding lack of guidance regarding execution so, let’s talk about what it looks like to actually do the work of audience research.

(I’ll introduce the topic now, then we’ll discuss the bulk of it in the next chapter.)

To gain a complete understanding of your people, you’ll want to focus on two key terms: demographics and psychographics.

Demographics include tangible facts, such as: age, gender, income level, education, geographic location, etc.

For instance, if you’re developing a complex strategy game, you might assume your target demographic to be older players with a higher education level.

Psychographics, on the other hand, delve into more subjective areas. They include interests, hobbies, lifestyle, values, and personality traits. This is the gold mine.

To stick with the earlier example, our strategy game might turn out to appeal to players who enjoy intellectual challenges, problem-solving, and have a competitive spirit — regardless of the player’s age, income, or other demographic factors.

In fact, demographics are completely incapable of providing us with those insights.

Psychographics asks questions like:

- What are their likes, dislikes, interests, and gaming habits?

- Do they enjoy horror games? Why?

- Are they competitive players who enjoy a challenge?

- Or perhaps they are social gamers who love cooperative play?

In our series, The Entrepreneur’s Quest, we introduce two characters (Larry and Jasper), whom we use to explain the concept of “avatars.”

In this series, we look to those characters again, and imagine what it might be like if they represented gamers.

Let’s imagine that Larry is a 25-year-old IT professional, who loves strategy games and relishes the challenge they present. He’s competitive and enjoys playing games that make him think.

Jasper, on the other hand, is a 40-year-old entrepreneur with a penchant for games that offer immersive narratives, complex characters, and combat systems with high-skill ceilings.

You likely wouldn’t make the same game for both people.

In the beginning, you’ll be guessing at who your audience is, and that’s ok — we have to start somewhere.

But we don’t stop at that guess.

Once you have that initial guess at who your ideal player might be, it’s time to roll up your sleeves, do some research, and put your assumptions to the test.

But how do you actually begin that research?

How do you parse that data and learn those critical insights?

We’ll talk about that next…